At different times and places, a white feather has carried different meanings. For those inclined toward New-Age, the presence of a white feather is proof that Guardian Angels are near. For the Viet Cong and NVA Regulars who were his prey, the “Lông Trắng” (“White Feather”) symbolized the deadliest menace of the American war effort in Vietnam, USMC Scout Sniper Carlos Hathcock, who wore one in his bush hat. Following the Battle of Crécy in 1346, Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales, plucked three white ostrich feathers from the dead body of the blind King John of Bohemia. To this day, those feathers appear in the coat of arms, of the prince of Wales.

The Edward and John who faced one another over the field at Crécy, could be described in many ways. Cowardice is not one of them. For the men of the WW1 generation, a white feather represented precisely that.

In August 1914, seventy-three year old British Admiral Charles Cooper Penrose-Fitzgerald organized a group of thirty women, to give out white feathers to men not in uniform. The point was clear enough. To gin up enough manpower, to feed the needs of a war so large as to gobble up a generation, and spit out the pieces.

Lord Horatio Kitchener supported the measure, saying “The women could play a great part in the emergency by using their influence with their husbands and sons to take their proper share in the country’s defence, and every girl who had a sweetheart should tell men that she would not walk out with him again until he had done his part in licking the Germans.”

The Guardian newspaper chimed in, breathlessly reporting on the activities of the “Order of the White Feather“, hoping that the gesture “would shame every young slacker” into enlisting.

In theory, such an “award” was intended to inspire the dilatory to fulfill his duty to King and country. In practice, such presentations were often mean-spirited and out of line. Sometimes, grotesquely so.

The movement spread across Great Britain and the Commonwealth nations and across Europe, encouraged by suffragettes such as Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel, and feminist writers Mary Augusta Ward, founding President of the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League, and British-Hungarian novelist and playwright, Emma Orczy.

Distributors of the white feather were almost exclusively female, who frequently misjudged their targets. Stories abound of men on leave, wounded, or in reserved occupations being handed one of the odious symbols.

Seaman George Samson received a white feather on the same day he was awarded the British Commonwealth’s highest military award for gallantry in combat, equivalent to the American Medal of Honor: the Victoria Cross.

Seaman George Samson received a white feather on the same day he was awarded the British Commonwealth’s highest military award for gallantry in combat, equivalent to the American Medal of Honor: the Victoria Cross.

Gangs of “feather girls” took to the streets, looking for military-age men out of uniform. Frederick Broome was fifteen years old, when “accosted by four girls who gave me three white feathers.”

The writer Compton Mackenzie, himself a serving soldier, complained that these “idiotic young women were using white feathers to get rid of boyfriends of whom they were tired“.

James Lovegrove was sixteen when he received his first white feather: “On my way to work one morning a group of women surrounded me. They started shouting and yelling at me, calling me all sorts of names for not being a soldier! Do you know what they did? They struck a white feather in my coat, meaning I was a coward. Oh, I did feel dreadful, so ashamed.” Lovegrove went straight to the recruiting office, who tried to send him home for being too young and too small: “You see, I was five foot six inches and only about eight and a half stone. This time he made me out to be about six feet tall and twelve stone, at least, that is what he wrote down. All lies of course – but I was in!”.

James Lovegrove was sixteen when he received his first white feather: “On my way to work one morning a group of women surrounded me. They started shouting and yelling at me, calling me all sorts of names for not being a soldier! Do you know what they did? They struck a white feather in my coat, meaning I was a coward. Oh, I did feel dreadful, so ashamed.” Lovegrove went straight to the recruiting office, who tried to send him home for being too young and too small: “You see, I was five foot six inches and only about eight and a half stone. This time he made me out to be about six feet tall and twelve stone, at least, that is what he wrote down. All lies of course – but I was in!”.

James Cutmore attempted to volunteer for the British Army in 1914, but was rejected for being near-sighted. By 1916, the war in Europe was consuming men at a rate unprecedented in history. Governments weren’t nearly so picky. A woman gave Cutmore a white feather as he walked home from work. Humiliated, he enlisted the following day. In the 1980s, Cutmore’s grandchild wrote “By that time, they cared nothing for [near-sightedness]. They just wanted a body to stop a shell, which Rifleman James Cutmore duly did in February 1918, dying of his wounds on March 28. My mother was nine, and never got over it. In her last years, in the 1980s, her once fine brain so crippled by dementia that she could not remember the names of her children, she could still remember his dreadful, lingering, useless death. She could still talk of his last leave, when he was so shell-shocked he could hardly speak and my grandmother ironed his uniform every day in the vain hope of killing the lice.”

Some of these people were not to be put off. One man was confronted by an angry woman in a London park, who demanded to know why he wasn’t in uniform. “Because I’m German“, he said. She gave him a feather anyway.

Some of these people were not to be put off. One man was confronted by an angry woman in a London park, who demanded to know why he wasn’t in uniform. “Because I’m German“, he said. She gave him a feather anyway.

Some men had no patience for such nonsense. Private Ernest Atkins was one. Atkins was riding in a train car, when the woman seated behind him presented him with a white feather. Striking her across the face with his pay book, Atkins promised “Certainly I’ll take your feather back to the boys at Passchendaele. I’m in civvies because people think my uniform might be lousy, but if I had it on I wouldn’t be half as lousy as you.”

Private Norman Demuth was discharged from the British Army, after being wounded in 1916. A woman on a bus handed Demuth a feather, saying “Here’s a gift for a brave soldier.” Demuth was cooler than I might have been, under the circumstances: “Thank you very much – I wanted one of those.” He used the feather to clean his pipe, handing it back to her with the comment, “You know we didn’t get these in the trenches.”

Private Norman Demuth was discharged from the British Army, after being wounded in 1916. A woman on a bus handed Demuth a feather, saying “Here’s a gift for a brave soldier.” Demuth was cooler than I might have been, under the circumstances: “Thank you very much – I wanted one of those.” He used the feather to clean his pipe, handing it back to her with the comment, “You know we didn’t get these in the trenches.”

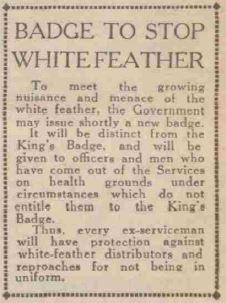

Inevitably, the white feather became a problem, when civilian government employees began to receive the hated symbol. Home Secretary Reginald McKenna issued lapel badges to employees in state industries, reading “King and Country”, proving that they too, were serving the war effort. Veterans who’d been discharged for wounds or illness were likewise issued such a badge, that they not be accosted in the street.

So it was that the laborer from the small town in Germany was sent to kill the greengrocer from St. Albans, spurred on by their women and the whole sorry mess driven by the politicians who would make war. The white feather campaign was briefly revived during WW2, but never caught on to anything approaching the same degree as the first.

The English poet, writer and soldier Siegfried Loraine Sassoon, CBE, MC, was decorated for bravery on the Western Front. Sassoon would become one of the leading poets of WW1. Let him have the final word.

“If I were fierce, and bald, and short of breath,

I’d live with scarlet majors at the Base,

And speed glum heroes up the line to death…

And when the war is done and youth stone dead,

I’d toddle safely home and die – in bed.”

Siegfried Sassoon

Other than the aspersions on Secretary Bryan, these revelations came as news. I was particularly pleased to the the appeal to altruism in the hand-printed letter-cum-feather. Self-esteem is much more difficult to reshape into a will to get shot so that the banks that made loans to belligerents not suffer the embarrassment of defaulting on bonds sold to the public. French banks created a panoply of “Emprunt!” posters designed to separate a collectivist from his money.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great telling of this lesser-known part of WWI. It is a great reminder that we never know the full story with anyone, or what is going on in their lives. Nothing is as it appears! Love your blog – thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Nicely told; I fear that base ignorance and stupidity still drives many people the world over. Sassoon was an interesting character – a decorated war hero with a brilliant mind who published an article declaring that he could no longer support the war’s aims. The authorities decided that the best way to handle this was to declare that he was mad.

LikeLiked by 3 people